Just repeating what I said in my other posts: this is not a live post, I was busy when I made this project, so I’m coming back now and writing it all down…

Anyways, onto the project itself:

This summer (2016), I’m working on a project that I’m going to apply for a science fair with. Without going into too much detail, a big part of my project revolves around having data, specifically pictures. In fact, the amount of images that I need is on an order of magnitude of a million… Not some small feet feat.

The best/worst part of this is that these photos need to be collected by your’s truely, as there is some other information that works alongside photos to make the data usable.

At the beginning of the project, I just picked up some pieces of metal, and scrapped together this:

If you can see past the table clutter (sorry about that) you can see that this robot is a very simple robot with a tank thread drive train, and a web cam for collecting photos.

This robot worked, but the Raspberry Pi controlling the robot could only take 1 photo every 7 seconds or so, making this a VERY inefficient little system. Not only that, but this robot was back heavy, so I had to strap a can of coke onto the front to even the weight out:

I couldn’t take it anymore, and I ended up designing my own robot from scratch…

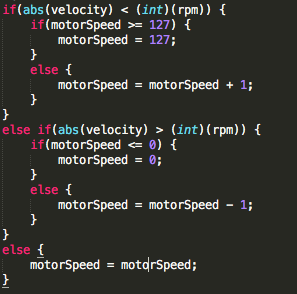

First thing I did was to decide on what I was going to keep from the old robot. I wanted the wheels (I figured 3D printing new ones would take way too long) and all the electronics, except for the camera hardware (more on that later). After that, I hopped into AutoCad and started to design the bot:

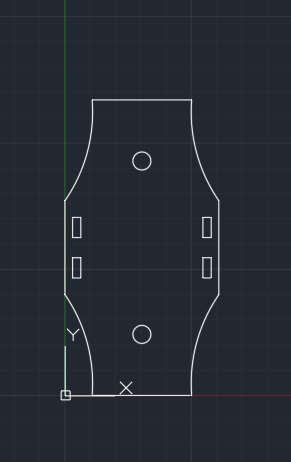

One of the main focuses of this bot was to make sure that center of gravity was close to the bottom, to reduce the amount of wobble in camera and top part of the robot. For this reason, I wanted the bottom of the robot to be a shallow box where I could put the motors, battery, and arduino: which should be enough to move the center of gravity closer to the bottom:

As you can see, it is a very simple box design (that took painstakingly long) with holes cut out for the motor mounts, the neck of the robot, as well as some holes for running wires out of the base.

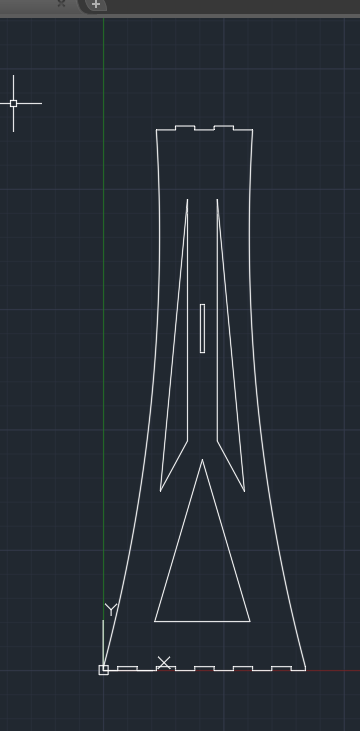

Next thing was the neck, or what elevated the camera from the base. I, again, wanted to have a very slim build, which would play its role in lowering the center of gravity. Looking back on it, I wished that I had left some more material in the neck, but it works:

Finally, the cherry on top was the top mounted plate. I was not a big fan of having a photo every ~7 seconds, as that is just inefficient. Luckily, my adviser (shout out to Mr. Medvitz!) hooked me up with a pair of these Mobius Actioncams. These are similar to the ever popular Go-Pro, and they are capable of recording at 60 fps. And because I have a pair of them strapped onto my robot, they would have an effective 120 fps. That means that this robot can take the same number of photos the previous robot did in 14 minutes, but do it in one freaking second.

You gotta love technology.

Anyways, here is the design for the top plate:

Then it was off to school to laser cut these Bad Larry’s out.

It should be noted that I used and designed these pieces to work with 2.032mm (or 0.080″ if you don’t have a burning love for SI units) acrylic.

Finally assembled:

Note: I had to jerry-rig some tank threads out of duct tape because it turns out that the robotics kit I stole the wheels from has more friction in the system than my feet on the ground when my parents drag me out shopping. This resulted in the robot just pushing the front wheels around, and an inability to handle bumps of any nature. By connecting the pair of wheels by some duct tape, I am losing energy and potentially battery life, but all the wheels are powered and the robot can now handle almost every surface type.

I know that this robot is not very pretty or even that “impressive.” Given more time and materials, I would have preferred to have made a much more elegant robot with a 4 wheel drive, maybe even geared for speed. However, given that this robot was thought of, precisely measured, designed, cut, and assembled within a matter of days, I’m happy with the results.